Far from the beach, but still surrounded by treasure of all kinds just ready to be found, looked at, gloated over, gleaned and swiped or simply created! Here are my latest finds....

Wednesday, March 30, 2022

Pink Perfection...

Springtime flowers never fail to amaze with their variety of colours and shades, shapes and forms, textures and touch... not forgetting smell. As the clocks move forward, Nature follows or perhaps leads the way towards the changing seasons. Whether they are found locally, or are hybrids from countries afar, these blooms chase out the last remnants of Winter. Some seem bold and jaunty, whilst others appear more subtle...

Delicate petals are set out in tightly-spun intricate layers, like a flurry of tissue paper...

Or have a simplicity in shape that is offset by an incredible intensity of colour.... all of which led me to wonder how flowers can produce such complexity of colour and shade. How is this actually done? Flower form, fragrance and colouring are means to lure in passing pollinators and seed dispersers but how are these all brought about?

The intricacies of Nature never fail to amaze me and although there is a scientific explanation for the colouration of flowers, this does not seem to cover the almost magical quality of this process or indeed many of the others found in the natural world around us, all taken for granted and rarely questioned by we humans.

Plant pigments are responsible for colouring, the most obvious of which being green, of course, due to chlorophyll. These chemical compounds all contain molecules that will selectively absorb certain wavelengths of light whilst reflecting others. Although there are three main categories of pigment - flavonoids, carotenoids and betalains - which form the vast range of colours we so appreciate in flowers, we cannot see many of the others available to other 'lesser' species.

The humble bee can actually pick out a colour that simply does not exist for humans as it is beyond our visual capacity - combiniing yellow and ultraviolet light to produce what is referred to as 'bees' purple'. On the subject of bees, I did also wonder about how they actually produce and deposit wax, but that is another story... In the meantime, I can enjoy some pink perfection in soft, ruffled petals that highlight a beautiful man-made backcloth.

Tuesday, March 29, 2022

Early Evening (and almost Night !) in.... Cimetière du Nord...

With the changing seasons, a beautiful site that I often return to is that of the « Père-Lachaise rémois », otherwise known today as the Cimetière du Nord de Reims. The oldest parts of this cemetery, which dates back to the late 18th century, still house many of the graves and individual chapels whose plots were set in place in the decades following its inauguration.

Built in 1787, just before the French Revolution, this garden à l'anglaise setting was conceived in response to the same dilemma that confronted most towns and cities; how to bury their dead in a dignified, safe manner. Communal graves set intra muros could no longer offer any kind of satisfactory solution and were to be banned definitively. Hence, some 17 years before the grand Parisian necropolis, the provincial Cimetière de la Porte Mars was opened, just outside the city walls, and later to be renamed Cimetière du Nord; the oldest cemetery of Reims.

Although many of the original monuments such as the Chapelle Sainte-Croix survived the ravages of the French Revolution years from 1789, like much of the city, the cemetery suffered considerable damage during the Great War of 1914-18. Indeed, the chapel itself was virtually destroyed and was under threat of demolition until classified as a Monument Historique in 1927.

Nevertheless, in the post-war years, both city and cemetery were rebuilt and it is difficult now to imagine the loss and devastation of that period. The earliest sections of the site - divided into cantons (as opposed to more familiar term - divisions) - make up a place of great beauty and tranquility, with the paths winding between trees and what could be called a 'respectable' amount of greenery.

Only when I visited Brompton cemetery in London last month, did I realise just how well its little French equivalent here in Reims stands up to a comparison with the vast and renowned necropoles of the 'Magnificent Seven'. The atmosphere is just as powerful yet peaceful, the monuments equally ornate, moving and somewhat mysterious in their age and gentle decay as their English counterparts and the wildlife likewise magical, in Spring, Summer or Winter. Last week, overwintering butterflies were dancing around the gravestones, flickering in the sunlight, birds cheerily chirping away, indifferent to any sombre mood the tombs may exude, and to the cats prowling around in the undergrowth, snaking their way between gravestones.

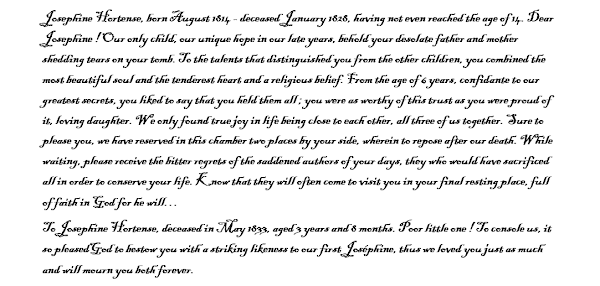

Each time I come here, new details seem to emerge from the old, catching my eye for the first time or retaining my gaze yet again. And so it is with the tomb below, which not only catches my attention on every visit, but also causes me to catch my breath. From an inscription that is gradually being lost to time, there is an expression of emotion has in no way diminished with the years. Indeed, such is the extent of the sadness that emanates from this grave that I can only stop to read it again and again. Whilst all graves hold infinite stories of loss - with love and life itself fully experienced and enjoyed, or denied, thwarted, cut short - rarely have I seen this expressed so clearly.

The pain of the parents of the first Joséphine, who suffered the loss of their beloved daughter at the age of 14 years, was to be relived and heightened by death of a second Joséphine in early infancy. Their sorrow seeps through the stonework still... reaching out to us.

To make this sadder still is the enigmatic blank first panel on the family tombstone, indicating that perhaps no relative of the famille Clément-Cochon was able to complete the inscription to show that parents and daughters had finally been reunited in this resting place as had been their own wish and expressed promise to their first-born.

On every visit, I try to shrug off this tale as a heavy shroud since I do not want to dwell on such sadness, but am inevitably drawn back, like a moth to a flame. So this time, I thought I would inscribe it in this virtual expanse and pay my respects as a stranger, over time and space, to a family of the long-distant past whose sentiments we can still sense in the present but pray will never experience ourselves.

Death is part of Life and vice versa, and it is therefore enheartening and wholly appropriate that all cemeteries are focal points for wildlife in all shapes and forms; even the lichen and moss that forms on the stonework underlines the movement of Life! Naturally the violets and primroses flowering on the grassy patches between plots add a jollity that you cannot escape, and reflect some of the ornate floral carvings of the gravestones themselves.

Whilst the 19th century symbolic staples are here; broken urns, upturned torches, hour-glasses, the odd weaping angel, Egyptian faces and a collection of owls, I particularly love the clasped hands. On my latest visit I noticed a hand detail that actually made me laugh, as two hands each clasp a wreath at the extremities of a sarcophagus yet both appear to be attached to one very long extended arm that runs along the entire length of the crest!

Well, for all that the last laugh was very definitely on me, for as I walked around the cemetery at the end of the afternoon, I failed to notice the time and so when I went to leave... the very tall, imposing iron gates were firmly shut and held in place by an equally impressive padlock! Having minimal battery on my phone, I quickly made a desperate call to my daughter with strict instructions to inform the fire brigade or police to get me out before nightfall! About an hour later, I was set free but have to admit it was a special moment to have the cemetery to myself... and yet again, my visit underlined the wise words used by Hugues Krafft as the motto for the Société des Amis du Vieux Reims;...... Urbium sacra senectus » : all that is ancient in a town is sacred.

Friday, March 4, 2022

Beastly Goings-on in the Victoria and Albert Museum - The Dacre Beasts...

Whilst in the Victoria and Albert Museum, I came across the following four imposing figures, guarding the steps leading to one of the exhibit rooms of the British Galleries. The Dacre Beasts, as they are known, are the last remaining specimens of Tudor heraldic carving dating back to the reign of Henry VIII. Standing tall and proud at around 6ft in height, the red bull, black gryphon, white ram and crested dolphin tower over the visitors, much as they must have done in their former setting in Naworth castle in Cumbria from the early 16th century. There, the beasts loyally stood below a ceiling decorated with paintings of the sovereigns of England in a sign of the allegiance of the Dacre family to the king, and thus highlighting the Dacre motto: « Fort en Loialte » (Strong in Loyalty). The name Dacre, is said to originate from an ancestor, Acre, who served in the siege of Palestine at the end of the 12th century…

Unfortunately, due to the tightening of financial circumstances in the 21st century Dacre family, the beasts were taken from their noble ancestral home that had been their ‘turf’, so to speak, for almost 500 years. In order to finance the upkeep of the Dacre castle, the descendant, Hon Philip Howard, felt obliged to generate funds through the sale of these historic pieces. Put up for auction at Sotheby’s in 2000, they were bought up by the V and A at a bargain price and are now visible to the public. The image of cattle to market did come to my mind at this point as I learnt of their history but at least they have been preserved, unlike the majority of similar works that have not survived to the present day. But if only they could talk ; what would they say of their change in identity, as one man’s insignia has become a rather anonymous, albeit impressive prize for a museum in the new millennium ? Although we visitors have gained in this exchange – I had certainly never heard of the Fab Four prior to my visit – they are perhaps a little lost in their present setting and may even be experiencing an existential blur.

Not so in the past, when the beasts set in their rightful domain were said to have inspired the illustrations of John Tenniel (1820-1914) for Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland during the artist’s stay at Naworth. Even those unable to see the actual beasts in flesh and fur within their castle setting would have seen printed works, driven by the Victorian thirst for Medieval imagery, heraldry and that Gothic touch. At one moment in their history, such illustrations were nearly all that was left of these magnificent carved forms when a devastating fire swept through Naworth in 1844, and yet the beasts escaped being reduced to charcoal. Nevertheless, whilst they may have thankfully lived to tell the tale, their current location renders them somewhat speechless and the small museum notice next to them does not tell us a great deal of their story. And what glorious beasts these are !

Carved from a single oak tree trunk by unknown craftsmen at the very end of the 15th century or first part of the 16th, these figures were made for Thomas Dacre (1467-1525), the 2nd Baron Dacre of Gilsland to reflect the dynastic alliance of two powerful families in Northern England through marriage. Indeed, each beast is a ‘supporter’ ; the creature that is shown on either side of the shield of arms. The exact function of the beasts is not known, for although they were apparently used in Dacre’s funeral, it is believed that they were intended to be displayed during tournaments to mark his considerable military skill and valour. Dacre had been a soldier in the last episode in the English Wars of the Roses during which King Richard III was defeated and killed by Henry Tudor in the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. He then went on to fight in the Battle of Flodden against the Scots in 1513, thus earning his reputation of staunch defender of the English crown, with the battle cry "A read bull, a read bull, a Dacre, a Dacre".

Thomas Dacre appears to have been a decisive man of action off the battlefield too, for in 1488 he eloped with Elizabeth Greystoke (1471-1516), a landed heiress. The Dolphin therefore represents the Greystoke family, as it carries the banner which displays Elizabeth’s arms – three cushions of argent – clasped between its decidedly fishy fins. Indeed, I must admit to having great difficulty in believing this was actually the portrayal of a dolphin – it looks more like a sizeable salmon, even given artistic licence ! The ram meanwhile, is the supporter of the De Multon family – from Ranulph de Dacre’s wife – and it bears a banner with a lion ‘passant’(walking with right fore paw raised) with three bars gules (heraldic tincture of red) upon argent (silver). The rather closely-shorn fleece and lack of horns make the ram look somewhat sheepish - not to say lacking in virility - but his very ostentatious male appendage would appear to define and display his ancestral power and position, presumably in a manner similar to (the rather more discreet) portrayals of Henry VIII in the royal portraits of Hans Holbein the Younger.

This same feature is shared by the two other beasts - the bull and the gryphon – whilst the Dolphin must content himself with a crown; fair is fair! The red bull of Dacre bears gilded horns, hooves and tongue in honour of his ancestry and wears a chained crown collar around his neck. He clasps the banner between his cloven hooves, displaying the arms of the Dacres – three white scallps on a red field. The black gryphon is the supporter of the Dacres of Gilsland and bears three rose chaplets (garlands of leaves with flowers) that are the 19th century arms of the Greystoke family. After the fire in 1844, the four beasts were repainted using Victorian colours that sought to recreate the initial tinctures, and the coats of arms were added at this stage. The architect in charge of restoration also saw fit to to gild the bull’s 'pizzle', an act that shocked the Victorian sensitivities of certain visitors to the castle at that time. I fear that the photos here may be banned due to ‘inappropriate content,’ which would be the ultimate dishonour to these fine beasts. Since they were on full public display in the Victoria and Albert, in all their finery, I trust they are ‘safe’ on this post too. How else can we learn about historic heraldry, with or without the infamous pizzle?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)