Far from the beach, but still surrounded by treasure of all kinds just ready to be found, looked at, gloated over, gleaned and swiped or simply created! Here are my latest finds....

Sunday, February 27, 2022

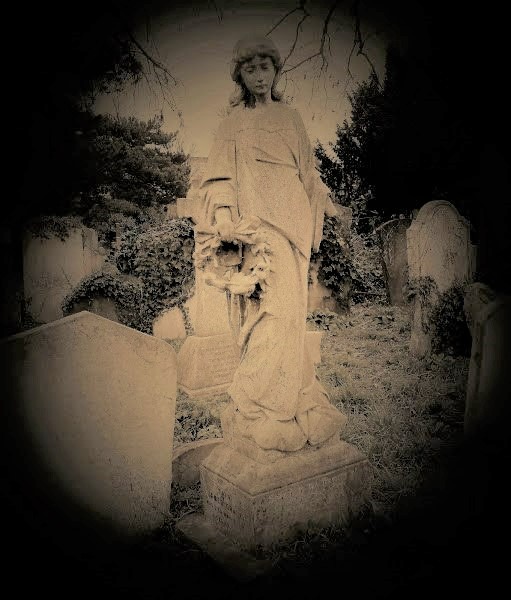

Angels in the Metropolis... Brompton Cemetery.

Tired of letting myself be drawn down the retail route – shops - I decided to explore one of the Magnificent Seven satellite cemeteries set around the capital in the first half of the 19th century. In fact, this was to be a commiseration prize to offset my disappointment at not being able to visit the Beatrix Potter exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum on on my recent trip to London...

Following my visit to Highgate cemetery a few years ago, I was eager to see how Brompton would hold up against its incredibly atmospheric, slightly older sister. Indeed, opened in 1840, Brompton closely followed Highgate (1839) but was some years behind the first great cemetery, Kensal Green (1833).

Greatly appreciated for its impressive architecture, imposing monuments and stonemasonry, I was particularly drawn to Brompton for its tombstones and the ‘contained and maintained’ wilderness that reigns throughout the site. Not surprisingly, the cemetery has featured as a backcloth in televised works and of course, the cinema, as has Highgate.

The peaceful, tranquil air of these sacred grounds devoted to past lives is magnified by the vibrant yet calming effect of the greenery of trees and plants which quiver with the life of the present. Early Spring sees the buds and flowers bursting out in defiance of the cold winds and rain of the winter months, as Life takes over from Death once more, in the eternal cycle.

Bold snowdrops and daffodils rise up again, bringing out the colour of the surroundings. Add to this the resident wildlife, and the magic is complete, with the plainly-visible robins, crows and squirrels of the daylight hours replaced, come nightfall, by a host of more elusive nocturnal creatures, when imaginations and spirits are free to wander. Whilst all share this sprawling territory with human populations, here is a haven for nature as much as a place of eternal rest for the Dead.

Whilst my thoughts and impressions ran free as I explored the alleys and somewhat overgrown plots, the phone (camera) simply ran out of battery. Infuriated, I had to resort to desperate measures and as the final photos did no justice to the unique mood and beauty of Brompton. I decided to use a special filter to mask the imperfections and try to make the best of a very unfortunate lot as my photos were so disappointing! Even if the result is rather eerie, not to say downright ominous, that was not necessarily intentional, and nor is it strictly representative of the atmosphere on a bright and blustery Spring day. Far from it, indeed!

Although a cemetery is burial site, and therefore intrinsically linked to loss and mourning, I find the older graveyards to be restful places that commemorate life past, enabling us to come to terms with life and existence itself and to understand social history more clearly. The atmosphere surrounding these old graves devoted to the long-departed is unique. The ageing stonework fittingly reflects lives ended centuries before ours were commenced. Names and dates that are barely visible today are often all that remain of lives forgotten, buried in time and blurred by anonymity. And yet they should remind us of the human condition, with regard to life and death.

We somehow forget that these beings were all individuals whose lives may mean little or nothing to us today, yet each had a life that was meaningful to them, however paltry it may have been. Each one experienced emotions, hopes and ambitions as we do today but we assume that these were somehow vastly different to ours today due to the different social and historical context. Shockingly high mortality rates in Victorian Britain meant that life for all was fragile and often short, whilst abject work and living conditions for the masses imposed a hopeless existence. Despite this, all individuals still clung onto life itself and were generally mourned when they left it.

Old cemeteries have always attracted me like a moth to candle-light, yet I had never known that there was actually a term for this – taphophilia – a ‘fascination and fondness for death rituals, funeral rites and cemeteries’. My attraction limits itself to the latter and only when the graves date back at least a century, preferably more. Any more recent, and the pain of loss pervades the atmosphere and seems to wind itself through the surroundings whereas the long-departed have long since been joined by their grieving loved ones. Furthermore, while I love to observe the inscriptions and symbolic decoration of graves and monuments, those from the 20th century generally do not have the same effect on me, possibly because timeless, flawless marble does not age or invite the growth of ivy, moss or lichen.

In Brompton, full Victorian symbolism is employed to reflect life, love, purity, death, loss, the soul and resurrection. Elements from the natural world, rich in meaning in previous centuries flourish in sculpted form with daffodils, lilies, birds, butterflies and snakes,to name but a few, all carved onto stone. Broken columns, inverted torches, draped urns and joining hands symbolize our earthly demise, the cycle of life and death and the journey to the afterlife. The traditional religious symbols abound, of course, with the Christian cross and the stepped cross, frequently inscribed with IHS but there are also many references to Ancient Egypt with obelisks, hieroglyphs and pyramidal forms. Unashamedly, I admit that one of my favourite symbols is the angel and I hoped that the ones here would be as evocative as those I saw in Birmingham, or indeed Highgate.

Behind the peace and beauty that we enjoy today in London’s garden cemeteries lies a less tranquil history. Indeed, these sites designed to honour the dead and soothe the living were born from a far less attractive need. The unprecedented population surge in early 19th century London meant that just as the city-dwellers were cramped together in dire, insalubrious conditions, so too were the deceased - piled together in vile, pestilential funeral grounds. Land, water and air were contaminated by putrid bodily fluids and infested by vermin which plagued the living and defiled the deceased.

Inspired by the impressive Parisian cemetery Père Lachaise of 1804, the seven large-scale funeral metropolis were designed to house London’s dead in a respectful, religious manner. Thus the construction of the Magnificent Seven was authorized by government, and commercial companies set about the task, eager to profit from a public prepared to pay the price for suitable burial plots to reflect social standing. Incidentally, I find it quite interesting that Paris should have been a source of inspiration in the solution to burying London’s dead, while London would later serve as a model for Baron Haussmann’s vision of a modernized Paris to accommodate the living!

Unlike Highgate, with its steep paths, slopes and meandering tracks that all add to its mystery, we still sense that Brompton cemetery was indeed constructed on flat land that had once been used for market gardens. Despite the numerous trees and undergrowth that conceal the skyline, the regular layout of the grounds makes itself apparent, underlined by the central tree-lined avenue that leads from the entrance on Old Brompton Road. In order to attract investors and customers, the design of the cemetery sought to impress, using features that recall St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. The neoclassical Great Circle, with central symmetrical colonnade, catacombs and chapel follows on from the avenue that acts as a nave. The eight-sided, domed chapel in yellow stone is at the heart of the cemetery’s design but was initially designed to be accompanied by two other chapels on both sides of the Great Circle.

Lack of sufficient funds skuppered these ambitious architectural plans and in fact the cemetery was forced to open in 1840 before the completion of the main chapel. Further financial difficulties arose when the catacombs failed to attract potential customers and shareholders were dismayed to have no return on their investment. Finally the Metropolitan Interments Act 1850 designed to enforce better provision for the internment of the dead enabled the government to buy Brompton, the first London cemetery to be nationalized. It is now managed by The Royal Parks and as such is the property of the Crown.

I was very pleased with my visit, especially as it made me appreciate just how much each cemetery has its own unique character and atmosphere and although the mood and magic of Brompton won me over, nothing for me so far could match Highgate and no angels have been as moving as the ones that mourn those departed in Yardley, Birmingham. Just as I left the cemetery, my digital camera suddenly gave up the ghost, and it started to pour with rain so I felt that my trip to Brompton had somehow been blessed. Perhaps there was an angel on my shoulder, though I would have settled for the jaunty little robin below! My good fortune did not end there either; I was able to go to the Beatrix Potter exhibition after all… It always pays to ask!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Leave a message - please share your ideas!