|

| On the site of the village of Fleury-devant-Douaumont which 'died for France'. |

As most of the regions in this part of France were the scene to extensive offensives during the First World War, it is almost impossible not to come across military cemeteries.

|

| Fleury-devant-Douaumont |

Although these graveyards once rose from barren land that had witnessed the worst war atrocities Mankind had ever inflicted on itself, today a strange tranquility reigns in these now wooded areas.

The surrounding landscape still bears the scars of the battles, but the effect is strangely beautiful as nature cloths and accommodates forms that can only be artificial.

Probably the largest of these areas is the battlefield of Verdun, which strikes you with its woodland beauty and shocks you with its stretch of military crosses that unfolds before you, into the distance.

|

| Verdun - In front of the Ossuary of Douaumont |

|

| Pocked-marked battle terrain in the mist. |

|

| Le train (convoy) on the Voie Sacrée. |

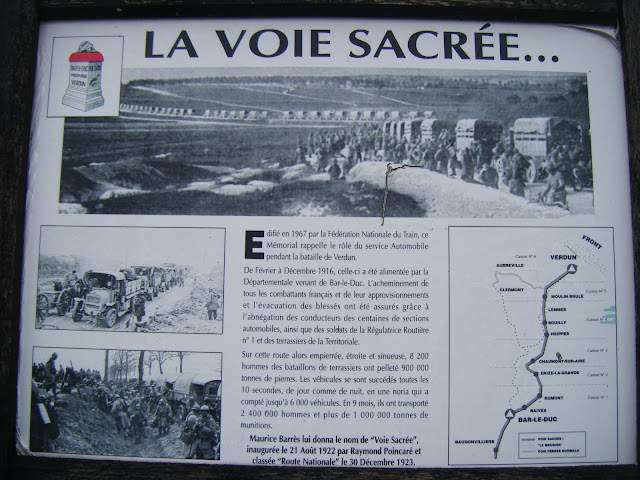

The Voie Sacrée, thus named at the end of the war by

Maurice Barrès, was to act as a vital artery to the French army in the Battle

of Verdun. A never-ending stream of men and arms circulated to and from the

Front, thus feeding the war machine, keeping it alive and literally supplying

it with lifeblood in this giant clash of the Titans. The gods at war here were

the Teutons and Gauls in a deadly racial feud that Lloyd George rightly termed

"one of the most gigantic, tenacious, grim, futile and bloody fights ever

waged".

|

| Large road-side sign on the Voie Sacrée. |

Erich von Falkenhayn, the mastermind behind the German offensive

called it Operation Gericht - meaning 'judgment' or the 'administration of

justice'. He hoped that this battle of attrition would "bleed the French

army white" and that such a strategic strike would deal a fatal blow to

the morale of the whole of France.

|

| Convoy on the Voie Sacrée |

Ultimately it was hoped that France, as "England's

best sword, would be knocked out of her hand". This, along with the

widespread use of submarine warfare, would literally starve Britain to

submission and would serve to crush the Entente whilst protecting the Habsburg

Empire.

In the whole deadly Verdun experience there could be

no victor or vanquished. There was no justice to be dealt, no judgment to be

made. Mankind lost in this battle since the only victory possible for civilisation

would have been peace. Yet war requires the cold process of dehumanisation

which leads men to simply act out its faceless battle tactics and moves, even

when a battle has lost all sense or logic. These gestures took on unprecedented

proportions of brutality, inhumanity and futility at Verdun in 1916.

|

| Monument to French Minister of War - whose name honours the Maginot Line |

The town of Verdun had always been of great historical,

strategic and symbolic importance to the French nation. The name itself comes

from the Latin 'verodunam' meaning 'strong fort'; even Attila the Hun had been

unable to penetrate this citadel in the fifth century. Ironically perhaps,

until 1648 Verdun was not even French as it had been part of the Holy Roman

Empire following the division of the Charlemagne empire in 843. What never

faltered over the centuries was Verdun's interest as a strategic point marking

the frontier between Gallic and Teutonic empires and acting as barrier, or

potential gateway, to Paris. To withstand attack, Verdun's antiquated medieval

defenses were updated during the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) to resist enemy artillery.

From 1670 the military engineer Vauban improved this defense further by a sophisticated

fortification programme. Unfortunately these were not sufficient to safeguard

the city in the first Battle of Verdun in 1792 which pitted the French Revolutionary

forces against the Prussian army. Captured by the enemy and released again,

Verdun suffered a similar fate in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870. As a result

of this humiliation, and in an endeavour to protect the eastern border, a

strong line of fortifications was built between Verdun and Toul, and between

Epinal and Belfort.

|

| Ex-Poilu soldier with a photo of his former self. |

As a salient, protruding into German territory, Verdun

was the tantalising northern gateway to the Champagne region, with Paris just 260km

beyond. Its defense was vital. A ring of 19 forts was constructed several

kilometres from the town shortly before the turn of the century, and further reinforcement

work was later carried out on the sites to the north and east of Verdun, namely

Fort Douaumont and Fort Vaux.

|

| Ossuary of Douaumont |

Despite its initial reputation for impenetrability,

Verdun was to have notable weak points for which it would pay dearly. Exposed

as it was on three sides, in theory Verdun needed all the fortifications it could

muster, especially if exposed to heavy German artillery. However the capture of

several Belgian defense forts had shown how ineffective such sites could be

when faced with such powerful munitions and it was felt that their supplies

could be put to better use. Indeed, by mid-1915, arms and equipment were required

elsewhere. The enemy attack had been countered on the Western Front yet

stalemate had ensued. As Verdun was ironically considered to occupy a 'quiet

zone' at that period, it was thus decided that many of its forts would be downsized

or dismantled (or even designated for destruction). Fort Douaumont was the most

notable example. In addition, Verdun's single-track rail system had been

weakened by German forces since 1914, and where it was exposed to enemy fire

could not be relied on for the transportation of significant supplies. Little

did the French realise, but as such, Verdun represented a deadly bottle-neck

trap set up to ensnare them, and was a strategic trophy for the Germans, ready

to be taken.

French intelligence knew that an attack was imminent

at the very beginning of 1916. The die had been cast. Reinforcements in men and

munitions were therefore hurried into the area, aided in their convoy by a

delay in the German offensive due to bad weather. Instead of the 12th February,

the attack was held back until the 21st February. Despite this delay the sheer

disparity in power on every level left little hope for the French. The Battle of

Verdun started in earnest with an apocalyptic 10-hour bombardment of the front

line. This "trommelfeuer" (drum fire) attack churned up the land and

pulverised its occupants. The deafening drum call, felt as a rumble even 160km

away, sounded the emergence of a living hell. Indeed, this baptism of fire and

blood was followed by advancing flamethrowers and storm troopers who cleared the

trenches of any remaining defenders.

|

| Veteran 'Poilu' soldier. |

The defeat of the French seemed to be

merely a question of days. In this extreme state of urgency the French Second

Army, under General Pétain, was summoned to the Front to reinforce the Verdun

sector. The

fort of Douaumont, not surprisingly perhaps, fell to the triumphant Brandenburg

regiment on the 25th of February. Its capture highlighted the errors in

strategic decisions on the part of the French war masterminds, notably under

General Joffre, and dealt a hard blow to French morale. Crueler still were the

physical blows which rained down on the actors in this very real theatre of war

through weapons and warfare devices which had barely been used before or rarely

to such an extent.

Even before the staging of this apocalyptic scene took

place in late February 1916, another frenetic activity had been triggered off well

behind the front line, several days earlier. It lead to a previously unseen

feat of logistics and would provide the French battleground with a vital

lifeline in the form of a serpentine convoy of men and material to and from the

Front. Following an emergency meeting on the 19th February the Automobile

Regulatory Commission was formed in order to respond to the army's transportation

requirements. It was decided that the modest road leading from Bar-le-Duc to

Verdun would be the centre of this mission, and immediately all concerned

ensured that the objective was achieved.

From the 21st February all horse-drawn

traffic and infantry were prevented from using the road, which was then devoted

solely to motorized vehicles. The narrow route itself was widened to

accommodate the two lines of movement, wholly focused on Verdun, there and

back. This continual flow never slowed over the following months; on the contrary,

the movement over the 75km distance built up in momentum and capacity. A slowdown

in the advance of Germans troops due to adverse weather conditions was used to

great advantage by the French. Just in the first two weeks of hostilities 132

battalions were transported along the route, in addition to 20,700 tons of

munitions and 1,300 tons of general supplies. In March 6,000 trucks passed each

day - roughly signifying one every 14 seconds, day and night. The drivers of

such vehicles were expected to work for up to 18 hours a day, for up to 10 days

in a row in order to maintain the rhythm. Any vehicle that broke down would be

hauled to the side of the road so as not to hinder the flow of traffic. To

counter the problems resulting from the poor road surface and the dire weather

quarries were opened up to supply stone chippings. When these proved inadequate

to maintain the most basic of standards for the convoy , stones were placed on

the route itself, to be crushed by the passing trucks themselves. Patrol planes

were flown overhead to avert or crush German attack.

|

| Monument to the Voie Sacrée |

|

| The same soldier with a bicycle, many decades later... |

'The Road', as it was

simply called during the battle, reflected the ingenuity and sheer

determination of all involved. In this manner, the Voie Sacrée led to the

logistic legend of 'French trucks over German rail systems'. However, this

legend is somewhat skewed since it does not give due recognition to the

narrow-gauged rail track that ran virtually parallel to the Voie Sacrée. Although

the Road did indeed bear the vast majority of traffic (approximately 78%), the

remainder was carried by the Chemin de

Fer Meusien. This modest line which transported supplies in food, horses

and munitions to the Front and brought the wounded back, was seconded by the

Nettancourt-Dugny line. In a prescient move, Pétain had ordered the

construction of this standard-gauge track in early March 1916 and it is was

duly completed and functional in a mere four months. Running beyond the reach

of enemy fire, it eased the pressure on the Road which had already reached full

capacity by the end of March. In this manner the Road gained in efficiency as

it was able to concentrate further on the flow of lighter freight and vehicles.

Together road and rail led to the rotation of some 2 million soldiers over the

following months and the heavy rumble of transport was ever-present.

|

| From the Monument au Morts at Meaux. |

Likewise, the deafening war machine of Verdun continued relentlessly. The Germans appeared to have the upper hand, with French soldiers outnumbered by almost two to one and armed with weapons that could not match the heavy enemy artillery. Nevertheless the French put up a brave defense and hindered the attack on the village of Douaumont on the 29th of February, making the most of bad weather to further accelerate the advance of convoys. When the village finally fell to the enemy on the 2nd March, German losses were considerable and revealed shortcomings in their strategy. Perhaps too sure of victory, the Germans had advanced fast in the initial stages of the offensive and had made themselves vulnerable. The front line had been transformed into a quagmire which resisted the movement of heavy German artillery, especially in hilly areas. Equally bogged down in mud, the German infantry exposed itself to French artillery on the opposite side of the river Meuse. Unable to progress frontally, the Germans decided to attack via the flanks of the hills of Le Mort-Homme and Côte 304. These offered a vantage point over the battlefield and also housed many French munitions and were the focus of a huge enemy attack followed by a counter-attack on the part of the French. The site was ravaged by the hostilities and the hills scalped to become volcanoes in a lunar landscape that swallowed up any human community or indeed any form of life.

Although now taken by the enemy, Fort Douaumont

remained a focal point of French concern on a both strategic and symbolic

level. The Germans managed to hold onto the fort, but at considerable human

cost. Despite the affectionate name bestowed on the fort - the "Old Uncle

Douaumont" - its capture certainly did not necessarily bring them much shelter

or luck as it turned out. It became a German safe haven for troops and

operational base in spite of the French Second Army's valiant attempts to

recapture it in late May 1916. However, the danger for the Germans came from

within as a relatively banal accident over a cooking fire set off grenades and

set alight to flame thrower fuel to then cause all the munition supplies to

explode in the fort. The catastrophic consequences were instantaneous and

resulted in the death of nearly 700 men. Although morale must have been crushed,

this did not deter the Germans in the mission to advance on Verdun. Their

offensive turned from Mort-Homme and Côte 304 and focused on Fort Vaux.

In

spite of the vast numbers of German shock troops( almost 10,000 men), and their

successful occupation of the top of the fort at the very beginning of June, the

bottom levels of the defense system were still courageously defended by the

French. Over the next five days, the ensuing hostilities in the labyrinthine

underground tunnels must have been worthy of an ancient tale from Greek

mythology, combined with the cruel weaponry of modern times. The French defense

was finally obliged to surrender when the soldiers simply ran out of water.

| ||

| The symbolic wounded Souville Lion. |

The

German victors of this stage of the Battle of Verdun could hardly be considered

to be winners as the losses suffered by both sides were horrendous. Since May,

General Pétain had tried to avoid the unnecessary loss of French troops by

remaining on the defensive. In addition, he rotated soldiers in a 'turnstile system' over several weeks so that the men gained in

experience or used that which they already had, yet maintained their morale. His

address to the troops in April 1916, "Courage ! On les aura !" was

intended to congratulate and above all encourage the continued war effort in a

period marked by devastating loss. Due to this system of rotation, 70% of the

French army passed through the "wringer of Verdun", whereas only a

quarter of the German forces did so. Needless to say, such trauma meant that

the majority of these war veterans, "les Poilus", were old before their

time - worn by the physical and psychological hardships.

|

| Lion de Belfort - Bartholdi (Statue of Liberty) - Paris |

German morale could hardly have been much higher than that of the French, yet they continued their southerly advance on the city of Verdun believing that their extensive use of diphosgene gas would enable them to overpower their last major obstacle, Fort Souville. This strong point had already been destroyed on the upper level, so on the 22nd June 1916 it was simply a question of taking the underground tunnels. However, the attack did not go to plan. The gas had dispersed with little effect on the French defenders who themselves were then able to annihilate the large concentration of German infantry heading to the fort by the use of heavy artillery. An additional aborted attempt on the part of the Germans to capture Fort Souville on the 5th August appeared to mark a new phase in the battle.

The failure to capture Fort Souville saw a shift in positions and strategy as the French took up the offensive whilst the Germans were forced to adopt a defensive approach. The German army was further disadvantaged by the need to respond to the Allied offensive on the Western Front by extra sending men and munitions. This was a strategic diversionary coup set up by General Joffre. By obliging the British war general Haig to bring forward the intended offensive in the Somme Joffre hoped to ease the pressure on the Second French Army at Verdun. The conflict commenced on the 1st of July rather than the initial date one month later. From this diversionary point of view the opening of the Battle of Somme may have achieved its objective, although it must be remembered that on the first day of hostilities alone one third of the British Army soldiers lost their lives. German resources at Verdun were further drained when troops were withdrawn in order to fight a Russian offensive on the Eastern Front. The Souville sector was yet again the target of another German assault on the 12th July, but the mission failed to take Fort Souville from the French. It was easily apparent that none of Falkenhayn's objectives had been achieved and his German troops were exhausted, having never left the hell-hole of Verdun. In August of 1916 Falkenhayn was replaced by von Hindenburg. Nevertheless this change of commander did nothing to alter the German position.

|

| Tombstone from a Muslim soldier - Douaumont |

Following Nivelle's

commands, General Mangin led the offensive that was directed at Fort Douaumont

in order to prise it out of the enemy's hands on the 24th October. The Germans

had already started to evacuate the fort, and the attack carried out by the

Regiment of Colonial Infantry of Morocco was a success. On the 2nd November

Fort Vaux was also evacuated and General Mangin continued his offensive to

reclaim territory that had been captured by the Germans from the outset of

their attack on Verdun. At the closing stage of the Battle of Verdun over 10,

000 German prisoners were captured and Hindenburg saw further retaliation as

futile.

|

| In the mist - headstones of the Muslim soldiers at Douaumont - all facing Mecca. |

The very land of the Verdun region itself was twisted,

torn and tortured beyond recognition. Villages were captured, recovered and

captured again, all traces of community and civilisation were choked, churned

up or simply obliterated in the process. This scarred landscape became known as

the Zone Rouge where whole villages and swathes of farmland had been swallowed

up and spat out again by the war machine. Contaminated with corpses of beast

and man alike, rendered toxic by chemical weapons and made potentially lethal

due to unexploded ordnance, the land was uninhabitable and unworkable. A string

of villages disappeared in this manner having "died for France" in a

series of tragic death throes. Fleury-devant-Douaumont exchanged hands 16 times

before it fell silent, and the calm and peace that reigns there today belies

the clamour and frenzy of the past.

A decision to plant trees on an extensive scale in the 1930's means that much of the battleground is tranquil woodland today. The craters and trenches that were scorched or scratched into the bare land during the hostilities now appear to be a curious undulations amongst the green foliage. Occasionally the land returns the remains of unknown soldiers to the present so that they may leave their burial ground in the wilderness to lay at rest in the necropolis at Douaumont. The strange form of the ossuary recalls that of a rounded bunker, or the curves on a combat helmet, with the central tower rising up like a vertical chrysalis. From the outside, the whole has a Germanic Art Deco feel which seems sober yet a little menacing in the absence of all colour except the overpowering grey of the stonework.

|

| Art Deco form of the Ossuary - even more oppressive in the mist... |

Through the small

windows looking inside the building are alcoves bearing the skeletal remains of

around 130,000 unidentified soldiers. The interior of the building appears more

like a classic spiritual place of peace and reflection, again in an Art Deco

style. Plaques on the walls and ceiling of the cloister commemorate the fallen,

whilst large black-and-white photos show veterans of Verdun, holding photos of

their younger selves during the war period.

|

| Bell tower - Douaumont |

|

| Cloister of the Ossuary at Douaumont |

In front of the ossuary,

leading down and away to the distance is the largest French WW1 military

cemetery. The Ossuary of Douaumont was created in response to the public need

of an official commemorative site to house the remains of the fallen soldiers in

dignity shortly after the Armistice. The first stone was laid in place by

Pétain in August 1920.

A monument to the Voie Sacrée was inaugurated in 1967 to mark the arrival point of troops coming from the rear to reach the plateau of Moulin-Brûlé, some 8 kilometres from the battlefields.

|

| Monument to the Voie Sacrée. |

|

| La Voie Sacrée |

In the central part of the curved wall,

behind the obelisk form is an inscription addressed to the veterans of the convoys

- road and rail - "Le train à ses anciens, à tous ceux de la Voie

Sacrée". From this central point two convoys set off in opposing

directions, representing the movement to and from the Front.

Both are led by a

small group of Poilu soldiers bearing either munitions on their way out to

battle or returning, loaded down with haversacks and leaning on walking canes.

Trucks, a horse-drawn cart and a locomotive feature on the frieze and all bear

the valiant soldiers who had fought, or were going to fight at Verdun.

There is

no other life form represented here - no trees or plant adorn the frieze of the

Voie Sacrée or detract our attention from the human activity.

|

| The train feeding the Front... |

|

| Returning from the Front on the Voie Sacrée... |

Apart from a distracting hum of traffic on

the road today, the calm of the tree-lined setting seems to make the memorial

of the Voie Sacrée even more sober, and the site more serene. The Voie Sacrée was

made a national route in 1923 and symbolic milestones decorated with sculpted

helmets of Poilu soldiers mark out the kilometres from Bar-le-Duc to Verdun. In

2006 the route was renamed the RD1916, in memory of its past.

Each year the Sacred Flame from the Tomb

of the Unknown Soldier is taken by relay-runners from below the Arc de Triomphe

in Paris to the Monument aux Morts in Verdun to mark the memorial ceremony of

the 11th of November; Remembrance Day.

|

| Above the entrance to the Ossuary of Douaumont |

Lest we forget...

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.

Next year will be the

centenary of the beginning of the Great War. I hope that after all of these

years it will be remembered as a tragic event brought about by the folly of

Mankind, irrespective of nationality. The film that best brings this aspect

home, for me, is All Quiet on the Western

Front. Everyone lost, on every side, in every way...