Soon a light festival will open along the paths of the Jardin des Plantes - this prestigous botanical setting in Paris - tracing the incredible diversity of the planet through the mammals and other creatures that have populated the land, sea and air over the millenia. Large illuminated structures, created by the China Light Festival, will honour these beasts of past and present, from the dinosaurs of 65 million years ago, to their modern descendants.

Having recently seen the preparations around the Ménagerie, I am very tempted to go, although I know the pleasure of the visitors could never be matched by that of any of the animals there. If only.

The magnificent Jardin des Plantes has to be one of my favourite places in Paris and is conveniently placed near the coach station so merits a visit every time I go to the capital. As you walk alongside flowerbeds, blooms and bushes under the alleys of plane trees, you hear the distinctive squawk of the African green parakeets that now colonise the gardens. Their mocking calls and brazen freedom is in stark contrast to the other exotic creatures housed but a few metres beyond.

On display in the Ménagerie is a population of beasts of fur, feather or scale, living in the safety and sanitation afforded by these enclosed spaces. Naturally, all the charges are well-cared for and their physical well-being is carefully supervised and without such structures, many species would simply already have become extinct.

However, the fact that certain species have relatively little to occupy, let alone entertain them can surely only sour our entertainment. Unlike our predecessors who had little experience and certainly no real understanding of such exotic examples of the natural world, we have the benefit of learning and a certain knowledge.

We may well be utterly enthralled and enchanted by the sight of latest arrivals –no one could be blasé when catching sight of the Snow Leopard cubs – but we are also now aware of what such capitivity signifies. The presence in the heart of the city of captive wild creatures is not normal, but nor is the fact that these endangered species originated in a wilderness that is equally under threat. We know the cost that such confinement incurs on these animals, and we also know that without paying this price for protection and perservation, many more would die out. The beauty on show – that animal magic - has always operated an obvious magnetic force that draws us in. However, the overwhelming sense of the ‘senseless’ in this existence of containment and confinement for some of the species is almost unbearable.

The profound ennui of many of the mammals was recognized centuries ago and yet today they pace their enclosures with the same crazy clockwork movement as they did then. It is heart-breaking to see the vacant expressions in their dulled eyes, but almost impossible to break this mechanical existence that offers little more than survival in a prison sentence for life.

This autumn’s babies are a joyful sight to behold and surely represent one of the unique joys in their mothers’ lives here in captivity and yet you cannot help but wonder what this life will be when these offspring reach maturity and no longer content themselves playing as they do at present and no longer need caring for. Both young and old will learn the reality of life imprisonment or simply resume it. Next to these mischievous cubs that scale the branches and mercilessly tease their mother, other adults wander ceaselessly and aimlessly up and down the cage, showing the direction that the young leopards’ lives will duly take. It seems tragic.

Initially, the Jardin des Plantes was created in the early 17th century as a royal botanical garden, le Jardin du Roi, tended to cultivate herbal remedies known as 'les Simples'. Under the direction of le Comte de Buffon (1707-1788) this was extended to become one of the most important research centres in Europe. Shortly after the French Revolution, the national research and educational institute for science was founded in the grounds; the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. In the same drive for public instruction in all affairs of the natural world, the Ménagerie was opened in 1794, under Bernardin de St Pierre, in order to enhance the museum collection with live specimens. Finally, the Galerie d'Anatomie Comparée was created just after the turn of the century.

The Ménagerie is thus one of the oldest zoos in the world and is very much a product of its time. As the French aristocracy literally lost their heads in the Revolution years, the numerous exotic animals from their private collections lost their homes. The nobility’s property and possessions were seized by the State, and likewise they were relieved of their noble beasts as these were taken off to the Ménagerie, soon joined there by other animals from the royal ménageries at Versailles and Raincy. As the public and fairground exhibits of animals were banned from the streets of the capital, the owners saw their charges confiscated and housed in the new structure in Le Jardin des Plantes.

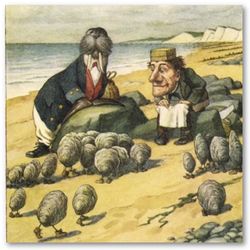

From a relatively modest 58 beasts, the Ménagerie collection expanded as the armies of the Convention period and then Napoleonic years took possession of further animals, receiving others as gifts or simply brought them back from foreign expeditions. One can only imagine how Parisians felt when encountering elephants, buffalo, camels, lions and the like at such close proximity. New enclosures were constructed to house the animals and display them to the eager spectators. For almost two decades the Rotunda was inhabited by one of the most famous ménagerie beasts; Zarafa the girafe. This ‘graceful and kind beast’, as her Arab name suggests, was sent to Charles X in 1826 with the aim of improving diplomatic relations between Egypt and France. Following her capture in southern Sudan, she was transported across the Mediterranean before being marched to Paris to the great astonishment of the crowds en route, not to mention the 600,000 visitors that flocked to see this strange beast in the Ménagerie. 'Girafomania' was thus born in 1827, triggering a range of merchandise to honour Zarafa.

Under the instructions of the naturalist Saint-Hilaire, director of the Muséum, the Ménagerie was increased in size in the 1860s and the enclosures improved in order to observe animal behaviour. Few people could have foreseen the dark period that was about to beset the Ménagerie. Whilst certain animals were killed by the hostilities during the Prussian invasion of the city, others were eaten by besieged, starving Parisians of the Commune in 1871. So it was that the elephants Pollux and Castor were lost in the most unfortunate circumstances…

The striking forms of the Vivarium (1926), the Monkey House (1936), and the Big Cat Enclosure (1937) employed innovative metal, materials and design, to startling effect, replacing certain structures that dated back some hundred years. The Art Déco sculpture of Paul Jouve completed the tone, yet by 1834 the opening of the Parc Zoologique de Paris had already had an impact of visitor numbers.

Since 1993 the buildings of the Ménagerie have been listed as historical monuments so whilst the larger mammals are slowly being transferred to larger institutions, more appropriate to their needs, this ancient site still fascinates the public, precisely due to its own unique story and its position in the history of Paris.

The enclosures that once were home to the showcase beasts of bigger dimensions, now accommodate smaller, critically endangered species. The former bear pits are now populated with the highly-popular Red Panda. Meanwhile other less-familiar species find refuge here – the bizarre Binturong (‘bearcats’) and the curious Pallas Cat, for example. However, the big cats still remain, captive and captivating, just as they were when Rilke wrote his poem 'The Panther', over a hundred years ago. Tragic.

The Orangutans stay on too, but seem to fare far better due to the social dynamics of their community – a group which has just increased in size with the birth of 'Java'. The hope is for a future reintroduction of many of the species preserved here, once their natural habitats have been repossessed and restored, but the powers of the Ménagerie - or any similar zoological establishment for that matter – are limited.

When I see the beauty of the beasts on display here, I feel sad that we humans cannot comprend that we do not actually possess the land we inhabit or indeed the Earth itself and should not be able to dispose of the other creatures as we see fit. Let's just hope that the festival Espèces en voie d'illumination that opens in November will throw a little more light onto the plight of our planet. Human-beings and orangutans share 97% of their DNA and yet Man is knowingly endangering the existence of this, our closest relative.